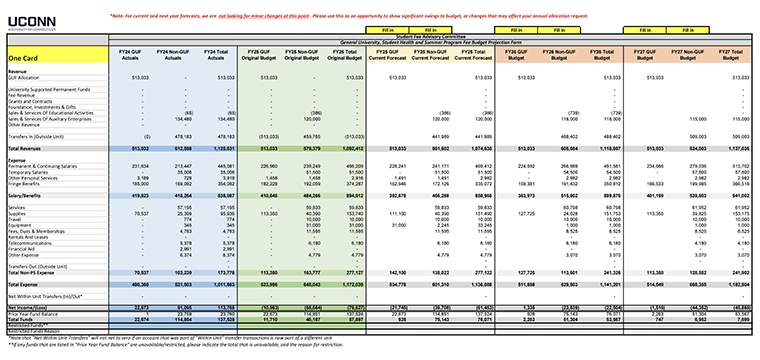

ColorID details technology underpinning prox, how it can be cloned

After nearly three decades in the field, the 125 kHz prox card remains one of the most widely used card technologies for electronic access. Still, it seems that many are unaware of more recent developments that now threaten the security of these cards.

In the latest installment of copmany's Spotlight Series newsletter, David Stallsmith, Director of Strategic Initiatives at ColorID, details prox technology, its susceptibilities and just how easy it is to clone these credentials in the field.

Prox, short for “proximity,” once offered a significant upgrade for users of mag stripe or Wiegand access cards, which have to be swiped through a card reader. Prox cards only need to be held near a reader to open a door, and can work through a wallet, purse or pants pocket.

"Since their operation was initially so mysterious, prox cards were generally thought to be as secure as they were convenient," writes Stallsmith. "For a long time, this was mostly true because the technology needed to clone a card was big and expensive."

Over time, however, the price for cracking a prox system fell dramatically making it far less prohibitive to compromise the credentials at scale.

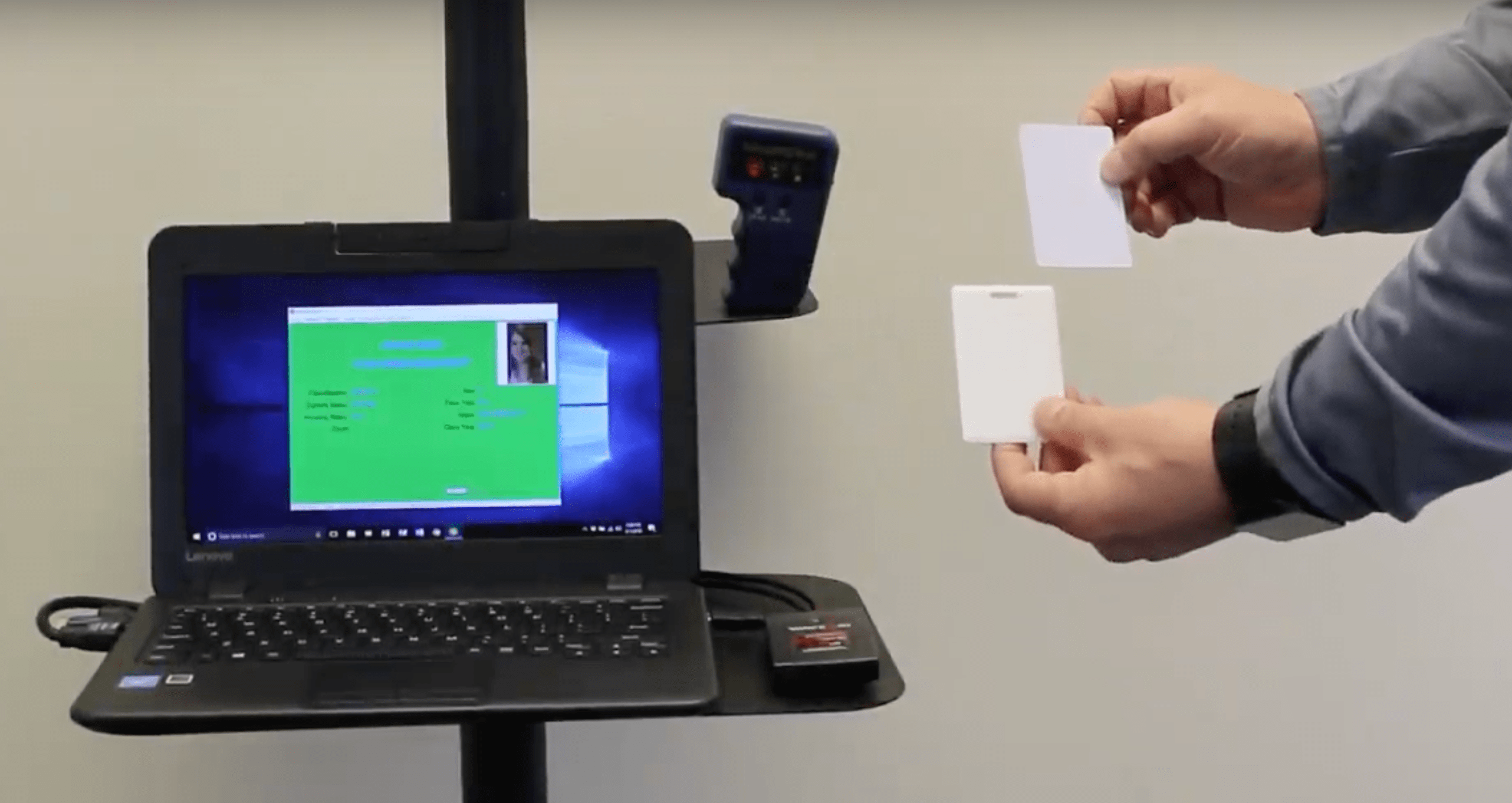

"Today, anyone can buy a device at a large online retailer for under $20 that can read the data from most 125KHz prox cards, store it, then write it to an unprogrammed card," explains Stallsmith. "There are also more powerful devices for under $500 that fit in a backpack and can read the data from a prox card several feet away, even if it's inside a wallet or purse. Both types of devices can be used to create unauthorized cards that the access control system cannot distinguish from officially issued prox cards."

These more readily available, inexpensive devices for cloning and copying prox cards has introduced a new threat level to the security landscape.

Legacy prox cards and readers were originally designed to communicate small amounts of data -- usually 8-16 digit card numbers -- in the 125 kHz radio frequency range. "Convenience and function were far more important design considerations than security, so data was transmitted in unencrypted form," explains Stallsmith. "This led to later attempts by manufacturers to bolster the security of prox technology by introducing simple data scrambling techniques or leveraging proprietary card number formats and ranges based on end-user licensing (e.g. Corporate 1000)."

These techniques, though initially effective, were ultimately a Band-Aid rather than a permanent solution. "Unfortunately, prox reading and writing technology is now so widely understood and available that the primary access card and reader manufacturers have lost their gatekeeper status," says Stallsmith. "The doors of those prox-protected buildings and systems are virtually standing wide open."

But what if your campus is leveraging prox? What can be done to mitigate the security risk?

"Prox-based access systems for doors and networks have relatively inexpensive end points, namely cards and readers," says Stallsmith. "In most cases, legacy prox cards and readers can be replaced with new, advanced technology cards and readers that communicate using modern encryption techniques. These new readers are typically interchangeable with legacy hardware, so they can be used with existing access control systems."

An increasing number of institutions are now ditching low-security credentials for more robust card technologies. The key to this migration, however, is to be proactive rather than reactive.

"Many corporations and institutions have migrated from legacy prox systems to more secure cards and readers. Some of these migrations were made voluntarily and in advance of any problems, but many were made after a breach revealed the unsuspected vulnerability," says Stallsmith. "Card and reader security is often overlooked for technology refresh scheduling, but the dramatic increase in prox system vulnerability should really move this item up in an organization’s security priorities."