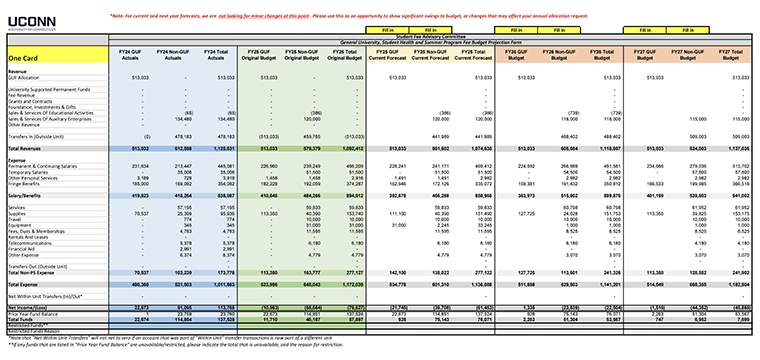

Mathematical templates enhance privacy and usability of biometric systems

Privacy risk … or a fear of the biometrics boogey man?

It's a question that came up in Denver late last year when the health club chain, 24 Hour Fitness, introduced a fingerprint-based check-in system to replace its membership cards.

The move added to the debate over whether systems that use fingerprint, face and eye images for identification can leak the information and create an invasion of privacy, according to a Denver Post article.

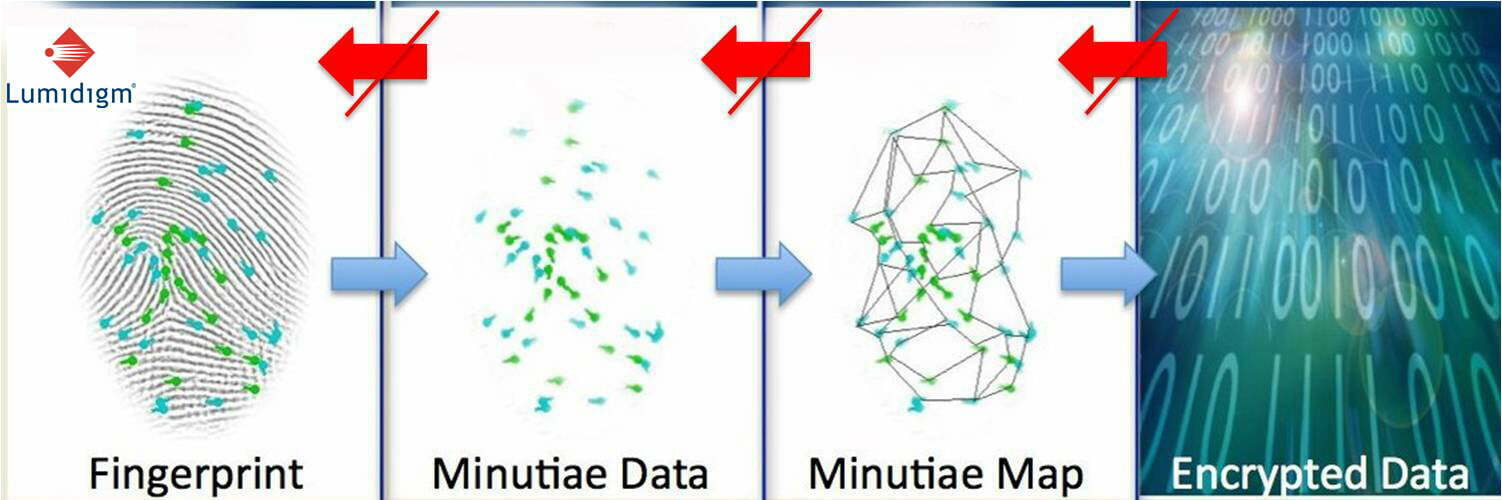

To set minds at ease, officials from 24 Hour Fitness pointed out a safeguard that biometric vendors often cite in defending their products: the system does not store actual fingerprint images but rather a numeric template that is a binary representation of specific points on the finger.

Industry experts say that when used properly, templates provide a secure method for identification that is privacy enabling. "It's not the technology, it's how you use the technology that really matters at the end of the day," says Phil Scarfo, senior vice president of sales and marketing for Lumidigm, an Albuquerque, N.M.-based biometric company specializing in fingerprint identification.

Though most biometrics systems rely solely on templates, or mathematical representations of the physical characteristic, the general public is not aware of this fact. "It is the misperception that people are storing fingerprint images in databases that creates concerns related to privacy," Scarfo says.

In every fingerprint, there are data points unique to that finger. "That constellation of points is what gets translated into this mathematical equation," says Scarfo.

The content for fingerprint, face and iris templates represents discreet visible artifacts or features, such as the corners of the mouth or shape of the eyes, says Michael Garris, supervisory computer scientist for the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in Gaithersburg, Md. "These points end up being feature points. Then you can compare the relative difference and displacement of those features between different samples," Garris says.

In its story on the 24 Hour Fitness debate, the Denver Post cites a September report by a blue-ribbon panel of the National Research Council calling biometric-identification techniques "inherently fallible."

Elaine Newton, senior adviser for identity technologies for NIST, disagrees with the statement. She says that it's more accurate to say that biometrics are "probabilistic," meaning that a biometric is not exactly the same each time it is collected. For instance, no two photographs of a person's face are precisely the same. This fact can lead to a degree of uncertainty when establishing an identity with biometrics.

Newton says that although templates on their own aren't perfect, neither are they inherently flawed. "For biometrics to be successfully fielded, they do not need to be perfect," she wrote in a 2009 report for Carnegie Mellon University. "Critical to their success is correctly designing the system."

Officials from 24 Hour Fitness said they took the extra step of encrypting the templates to provide an extra layer of privacy.

Encryption is a standard practice biometrics vendors take to guard against unauthorized viewing and reverse engineering templates, says Jim Bergen, Sarnoff Corp., a Princeton, N.J.-based technology firm that offers iris imaging products.

Whether encrypted or stored in the clear, most agree template data would be of very limited use to a hacker. "They wouldn't be able to figure out who those codes belong to anyway. They're just a bunch of ones and zeros," Bergen says.

The larger debate centers on the likelihood that an actual fingerprint, face, or iris image could be created from the limited number data points stored in a template. While some say it is possible, what that actual reverse-engineered image would look like is in question. A reverse-engineered image that could pass the biometric system's automated comparison would be far easier to create than one that would resemble a live sample that could pass human inspection.

In the case of iris templates, only the structure of the iris itself–the region between the pupil and the white part of the eye–is represented, Bergen says. That excludes eye color, size, shape and other features people typically use to recognize a person. "It is technically possible with certain kinds of iris codes to generate a sort of image from it, but it's an image that would be recognizable to an iris algorithm, not to a human being."

Still, some templates would be easier to crack than others. Proprietary templates rely on coding specific to an individual technology provider or vendor. Standard templates, however, contain information and coding common to several vendors, thus potentially making them easier to crack.

Industry experts cite several advantages to using a biometric template instead of an image. For one, there's dimensionality reduction, a reduction in the amount of space needed to store an image, Garris says. Templates make it easier to store biometric information on a smart card or other memory-restricted system.

Whereas a 1x1-inch fingerprint scan would contain about 250,000 bytes of data, a template of that scan would be smaller than 2,000 bytes. "A computer could work with those 250,000 bytes individually and try to match it for similarities or differences between other images similar in size … but that's a lot of data," Garris says. "In terms of storing and matching lots and lots of fingerprints, (with templates) you're dealing with a lot less data to have to store," he says.

Then there's the issue of speed. Being able to reliably authenticate a person's identity is significantly faster with templates. "Storing and transmitting images back and forth between a client device and a PC or back-end system is always a problem in terms of bandwidth and speed. Images are very large. Templates are very small," Scarfo says.

Another advantage is the privacy implications. Scarfo compares a biometric template to a constellation of stars. "How would you recreate an image or fingerprint from that constellation of points? You couldn't redraw the finger image. It's technically not possible."

Finally, experts say templates provide more opportunities for interoperability between systems. People may be using different devices from different vendors. By producing a standard template common to multiple vendors, a user can enroll in one system with one technology but authenticate in another system using a different technology.

While critics voice concerns that biometrics aren't well protected, proponents say fingerprint, eye and facial images were never really private to begin with. "We leave fingerprints behind on virtually everything we touch. Our face is always in public areas," Garris says. "Fingerprints and faces, they're personal things. But they're not private things."

Often, people confuse privacy with anonymity, Scarfo says. "People who want to fly on an airplane or enter a building have a right to privacy. But those granting us rights, for whatever reason, have a right to know who the heck we are," he says.

In the age of search engines and social networking, people are much more likely to give out private information–such as a social security number or an incriminating photo–that could be more damaging if it fell into the wrong hands than a fingerprint image would, Scarfo says. "There are all kinds of vulnerabilities we face these days, but I don't think biometrics is the biggest one."

You might say the concept of biometric templates dates back to the 19th century, when fingerprints were first used for identification and law enforcement purposes.

"If you have to look at two fingerprints side by side, that's not a terribly daunting task. Think about comparing that to a file filled with 1,000 fingerprints." says Michael Garris, supervisory computer scientist for the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

To streamline the process, Sir Edward Henry in the late 1800s devised the Henry Classification System for criminal investigations in British India. The system categorized different types of fingerprints by defining common finger points and other descriptive features, such as whether a print had an arch or loop pattern.

So instead of having to sort through thousands of fingerprints to find a match, a person might only have to search through the 100 that fit a particular category.

The same idea applies to biometric templates, except now it's computers instead of humans culling out matching fingerprint, iris and face characteristics.